Galt & Littlepage: A Family Affair

Jodi Littlepage-Mathura's Quest To Break The Second-Generation Curse And Preserve The Family Legacy

Jodi Littlepage-Mathura eased into a corner of the sofa, wrestling with her thoughts as Vale slept in an upstairs bedroom. Two or three times she glanced at the iPhone, playing her decision over in her head, growing nervous about what her mother had said. A small knot formed in her stomach. The call from Alastair Fenwick, her boss in Rio de Janeiro, came around 9 that morning. It lasted just eight minutes.

There would be no going back to Houston. She told Fenwick it wasn’t what she wanted. Houston had glistened with opportunity five years ago when it was just her and Kahlil. Now, Jodi wanted her daughter Viera and son Vale to spend weekends scuttling around Monos Island with their cousins, as she had done with her older sisters Zarna and Lara and younger brother John. There was also that feeling she couldn’t quite shake, like she owed this much to her father.

She was on a leave of absence from Schlumberger when Fenwick called, spending almost the entire year working part-time at Galt & Littlepage, the family business that had been a fixture of her August holidays. Michael Scott, a family friend she often turned to for advice, had recommended she submerge herself in the office supplies company her father had co-founded before she quit oil and gas for good.

Jodi’s father, John Littlepage, had never pushed the idea of her joining the company, although Mr Galt, his friend and co-founder, had nudged him about it several times when he realised none of Littlepage’s children had shown any interest.

It was Mr Galt who had to persuade Mr Littlepage to bring his son-in-law Stuart into the business. Still, Jodi’s mother Moira feared things could get messy in the two-family company and frowned on Jodi’s involvement.

But after a year in the business, something stirred in Jodi Littlepage-Mathura. Why hadn’t she given it more serious consideration before given what family meant to her? Galt & Littlepage was where she could make a difference. She knew she had something to offer the company.

From her early years as a geophysicist she had made a good impression on Fenwick and other Schlumberger execs, and steadily climbed the ranks. As recently as two years ago, she had been running major projects in the Texas oil patch. The money was good, yet Big Oil made Jodi, 34, feel invisible.

“In this industry, the business is bigger than any one person, so it’s easy to feel you’re not making a difference,” Jodi said.

By 2014 things looked grim. Oil prices plummeted to less than $40 a barrel. The economy took a hit. People all over the industry lost their jobs. Moira felt her daughter just had to wait it out like everyone else but, emotionally, Jodi had already walked away.

For three, sometimes four days a week, Jodi drove to the Long Circular Road offices of Galt & Littlepage, where she analysed sales numbers with the founders, looked over furniture designs with her brother-in-law Stuart, and set targets for staff with Jason, Mr Galt’s son, who had been working at the company since he left school.

Some evenings Jodi found herself giving Vale a bottle in front of an open laptop on her dinner table. She had little time to put all her ideas in place, ideas which she had been going over with Jason and Stuart. Numbers they needed to reverse. The slowdown in the economy had caught up. Galt & Littlepage had seen its second consecutive year of decline and was reeling from lack of foreign exchange.

Alone, Jodi thought more than ever about her father’s and uncle’s legacy. Mr Galt and Mr Littlepage were pushing 70, but the two had never fallen out. Jodi wondered if she, Stuart and Jason could make it work, when all her research told her second-generation businesses were doomed to flounder or fail. What would that mean for the families? Had Moira Littlepage sensed something they were all missing?

Jeffrey Kenneth Galt, born July 12, 1947, is a gregarious man, six feet two inches tall, and lean. He grew up in Fyzabad until he was 10, when his father, the late Ken Galt, sent him to live in Port of Spain with Peter Helps, the headmaster of Trinity College, his new school. Galt went on to graduate from Bishop’s University in Quebec in 1969 with a BA in business administration.

Possessing both an easygoing personality and sharp wit, he returned from Canada that year and took a job as a marketing analyst at Neal & Massy, the largest conglomerate in Trinidad, which, like all the banks and insurance companies at the time, was still run by foreigners seven years after independence. Galt excelled in the job.

His early days at the company coincided with the civil rights movement in the United States. At the time, the nationalist ideals of the Black Power Movement had also swept local boardrooms and pressure to instal local ownership in local companies saw Neal & Massy spin off the division that sold Xerox copiers into a separate company.

When division head Richard Waddell died unexpectedly, Sydney Knox, the man at the helm, knew better than to replace him with a foreigner, so he promoted Galt to general manager of Xerox Trinidad Limited, which was still majority-owned by Xerox’s parent company in the US. Neal & Massy held a minority stake.

In those days, businesses rented the copiers. Locals trusted the Xerox brand because Xerox was king of copiers across North America and Europe in much the same way IBM was king of typewriters and computers. Neal & Massy’s sales exploded. By 1985, Galt’s team was servicing hundreds of copiers all over the Caribbean.

“I had about 80 people working for me, and Johnny was the top sales rep,” Galt recalled. “That’s how we met.”

John Littlepage, soft-spoken and affable, had become friends with his boss after just six months with the division. Where Galt was charismatic, Littlepage was unassuming, a plodder who could let customers do most of the talking and get the sale anyway.

He and Galt first made money on top of their salaries when they hatched a plan to follow the stock market and buy up shares in WITCO, Angostura and the Workers Bank for between $2.00 and $3.50 a share.

One Friday evening, as both men and their wives looked over stocks at Littlepage’s house in Victoria Gardens, Galt brought up the business they’d been talking about starting. He’d grown tired of Neal & Massy’s politics, but Knox had tried to talk him out of it when he said he was leaving.

“Johnny, I think a grocery could do good,” Galt began.

“It could, but we don’t know anything about grocery,” Littlepage replied.

Johnny Littlepage crossed his legs, leaned back, locked his fingers behind his head.

“Jeff, why don’t we do what we know? Why don’t we forget about the grocery and go into office supplies?”

Right at that moment Galt locked eyes with Littlepage and for a few seconds neither of them said a word.

The business expanded the old-fashioned way: each man’s handshake was a promise to drive from one end of the island to the other end to deliver a ream of paper if that is what it took. To win customers, that is exactly what Johnny Littlepage and Jeffrey Galt did.

Mr Littlepage had made the right call with office supplies—paper and toner, mostly—but sales really took off when McEnearney, a supplier of office machines, showed up six months after they launched and persuaded them to sell plain-paper copiers.

But these were Canon copiers, and Canon was Xerox’s largest competitor so it took some time for Littlepage to agree to do it. They knew this business better than anyone. Still, Littlepage had always thought of himself and Galt as Xerox guys. For 17 years they had staked their reputation on that brand.

They started making annual trips to the Shopa trade show in Chicago and Las Vegas—which is how they discovered the Norstar brand and went into selling office furniture. Galt & Littlepage kept growing for the next 20 years. There were setbacks, of course, a few rough patches where they got turned down for loans or lost a client, but nothing unusual, nothing they couldn’t recover from. And they had help: they had taken four of Neal & Massy’s best salespeople with them when they quit, and their wives also worked in the business.

By 2010, the Galt & Littlepage client list included all the big names: government ministries, BP, Republic Bank, RBC Royal Bank, Guardian Life, Petrotrin and its predecessor Texaco. Then came a banner year in 2013 when sales peaked at $25 million. Thirty-odd years, business was thriving and the pair had remained friends. Galt thought he knew the reason they managed to stay together for so long.

“Most times partnerships break up it’s because of greed and jealousy,” Galt said. “Neither of us fall into that category.”

But Jeffrey Galt and Johnny Littlepage, whose attention to quality products and service had made a statement for an entire industry, hadn’t achieved this improbable success on account of their selling skills alone, or even their intrinsic knowledge of the business. A more reasonable explanation could be found in how Galt described the company’s culture.

“We are not bull-pistle kinda people,” Galt said. “In fact, sometimes they joke and call us Bobolee No. 1 and Bobolee No. 2, because we’re too soft. But in here it’s a family and we try to take care of one another.”

Three of seven original Galt & Littlepage employees are still there: Ian Lezama, the furniture manager, Miguel Luces, now a senior driver, and Jeffrey Fleming who runs their Freeport warehouse. Twenty-three of its 37 employees have been with the company for 10 years or more.

Yet for all their unwillingness to put profits before their employees, the founders readily admit that Galt & Littlepage hit a plateau about five years ago. With retirement staring them in the face it would be up to Jodi, Jason and Stuart to keep the company going for another generation.

Increased profits

It was a bold plan, but after the first nine months Jodi, Jason and Stuart felt like things were finally coming together. It helped that Mr Galt and Mr Littlepage had backed them up.

First, Jodi engaged Annette Rahael to coach all seven Galt & Littlepage directors on succession planning. Moira Littlepage cherished the love between the families, but they all knew her fears had merit. According to research by global management consulting firm McKinsey and Co., just one in three family businesses survives to the third generation.

With Rahael in play, Jodi turned her attention to the inner workings of Galt & Littlepage. She was driven by something she’d learnt at Schlumberger: success equals process. Flush with energy, she started working with Stuart, Jason and both founders to hammer out new policies meant to improve efficiency across the company. With the downturn in the economy, Jodi knew better systems would help, but she had one more card to play that she thought could reboot the company. When she finally got the call from an old contact she told the others about Guyana.

Flight BW601 touched down at Cheddi Jagan International at 7:20 that morning. Two hours later, in sweltering heat, Jodi Littlepage-Mathura arrived at Republic Bank’s largest branch, where she met Denys Benjamin, the manager of corporate services.

It had been a crucial part of Jodi’s plan to win business in the region and shore up the foreign exchange Galt & Littlepage needed to survive.

“Man, we had some wine right here in the office when that deal came through,” Jodi laughed.

But there was much more to do. Stuart had turned his attention to marketing. A man with an eye for style, he cared deeply about the image of the company he had given 16-plus years to, but he’d been swamped before Jodi came on board.

Now the two started working on Stuart’s baby: the first Galt & Littlepage showroom. Office-furniture companies had sprung up in Port of Spain, San Fernando and a couple of the business parks, but Jodi and Stuart liked their odds. They carried a fresh office suite that appealed to a new generation of employees. And Galt & Littlepage had a name.

The new showroom boasted lacquered wood and tiled floors adorned with contemporary Inscape pieces: long-legged, glass-topped tables, bouncy futons in bright colours, white lounge chairs with chrome legs tucked under desks on which stood reading lamps with see-through shades. Two rows of plush leather chairs hugged one of the walls, separated horizontally by a white wooden shelf that extended all the way across. In the corner, just as you entered, an accent chair covered in orange fabric commanded the attention of people passing outside.

Before the opening, Mr Galt joked that Jodi had forced them to give up good rent money for the space.

But that was until he saw how the glitzy showroom, filled with the warm glow of recessed lighting and spaceship-like chandeliers, burnished the “nothing flashy” image of Galt & Littlepage.

Just as Mr Galt and Mr Littlepage were thinking about retirement, the new showroom was the second generation’s way of saying to a now ultra-competitive office supplies industry “Game on.”

“Just as Mr Galt and Mr Littlepage were thinking about retirement, the new showroom was the second generation’s way of saying to a now ultra-competitive office supplies industry ‘Game on.’”

After three decades, Jeffrey Galt and Johnny Littlepage still sit side by side behind wooden desks in an office on the first floor. They still buy and sell shares together, and every day both men still leave for an hour and a half at noon to have lunch at home with their wives. Referring to Jodi, Jason and Stuart, Johnny Littlepage said he hoped they had taught them something about making a family business work.

“I have my son in the business and I am extremely proud of him,” Galt said, “but as far as I am concerned Jodi has been the missing link in the company.”

A black-and-white photo of Galt’s wife Elizabeth hangs on the wall above his desk. Across from it is a colour photo of six Littlepage grandchildren, five boys holding up signs next to a precocious Viera Mathura when she was two years old. The first sign reads: “Mess with her and you’re messing with me…”

It might easily have been a photo with Stuart, Jason, Jeffrey Galt and Johnny Littlepage holding that sign, with Jodi Littlepage-Mathura in the middle, CEO-designate of Galt & Littlepage and the first woman in the family to lead the company.

(In memory of Galt & Littlepage’s beloved employee Deborah Gilbert)

ONE MINUTE ENTREPRENEUR: JEFFREY GALT

Company: Galt & Littlepage

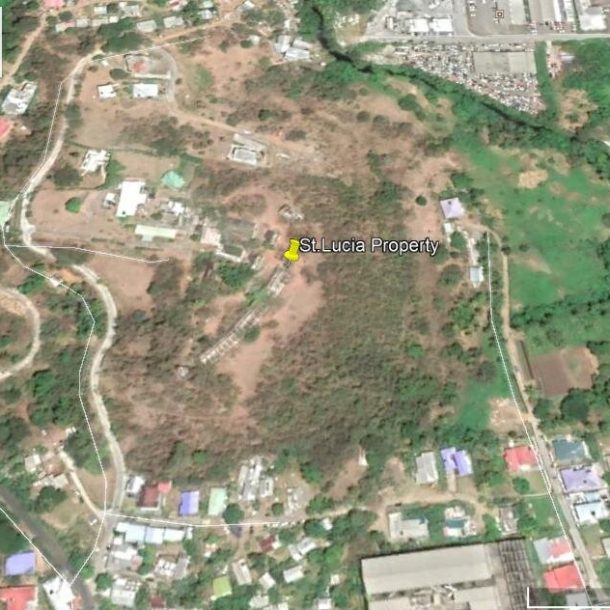

Location: St. James

No. of employees: 37

Industry: Office Furniture and Supplies

-

What’s one book every entrepreneur should read?

-

There’s a new book called "Shoe Dog" by Phil Knight, the founder and CEO of Nike. It's really an intriguing inside look into his story, about how he started with $50 and now owns a $30 billion business.

-

What’s one brand you admire?

-

I would go back to Nike because I’ve always followed their story. A local brand I have found interesting is Stag, and I say that because long ago Carib used to rule the roost and Stag’s tagline "A man’s beer" changed how people perceived beer.

-

How do you measure success?

-

The answer everyone will give is profits but to me I would say satisfaction. I feel if I am satisfied with what I achieved, if my customers are satisfied, and if my staff are satisfied then I have succeeded.

-

What's the best thing about running your own business?

-

You’re in control of your own destiny. You’re building your own identity from scratch.

-

The one piece of G&L furniture everyone should consider buying?

-

Treat yourself to a comfortable, ergonomically designed office chair. You’re sitting there 5-8 hours a day so get the chair.

CBTT’s Market Conduct Guideline | Privacy Policy